In these past few months I have delved into the the issues with modern-day life in regards to productivity and life balance. For my final white paper, I decided to examine how adapting deep work into the field of independent documentary production can allow you to organize your life’s work and make meaningful content to share with the world. I discuss the what, how, when, and why of deep work and end my paper with an interview with Ashley Brandon, a documentary filmmaker and full-time professor. Feel free to download and share.

Category: Interactive Communications and Media

-

It is not new knowledge that we are in a distracted world. As I have discussed in my previous posts, we are addicted to constant communication and screen time, so much so that it is difficult for many people to actually sit down and read something.

In Clive Thompson’s article Social Media is Keeping Us Stuck in the Moment, he contributes this addiction to distraction in part to the “reverse chronological design” that almost all news and social media sites utilize. In this design, the most recent posts and articles are at the top and you must scroll down to go back in time, which he says that this is damaging to how we consume information.

Thompson references Harold Innis’ On the Bias of Communication which was published way back in 1951 to show how this argument is not new. Innis attributed our “obsession with the immediate” to daily news, which was more disposable and discarded quicker than past forms of media.

To put it simply, constant news (whether it be in the form of tweets or news articles) is addictive. Thompson points out that it is not only making us more distracted, but more prone to believing in the “shiny new headlines” than actually researching a topic and understanding it.

What scares me the most about our addiction to technology is how it is hooking our children in from the get-go. In the article The Art of Staying Focused in a Distracting World, James Fallows interviews ex-Apple and Microsoft worker Linda Stone who now shares the dangers of distraction and being in a state of “continuous partial attention.”

Stone points out that in different situations we need to utilize different attention strategies. For example, a vital strategy is used when playing alone as a child and “you developed a capacity for attention and for a type of curiosity and experimentation that can happen when you play. You were in the moment, and the moment was unfolding in a natural way.” She argues, however, that the huge role that technology plays in many children’s lives does not allow for a child to develop these attention strategies.

From a young age, children learn through imitation. Kids are not inherently fascinated with phones and technology, they are fascinated with what mom and dad are fascinated with. Stone says that children learn empathy through eye contact, so what happens when their parent’s eyes are constantly on their phone? According to Stone, “What we’re doing now is modeling a primary relationship with screens, and a lack of eye contact with people.”

Stone believes that things are slowly getting better and the generations raised on screens are becoming more aware of the downsides of their attachment to a screen, but that we must create a capacity for a “relaxed presence” by doing activities that promote “mind and body in the same place at the same time.”

In Cal Newport’s second rule of Deep Work, he argues that these activities can not only aid in personal well being, but in your ability to focus on a task and work deeply. The chapter entitled “Embrace Boredom” outlines four ways you can train yourself to quell the urge to give into distraction.

Manage Your Breaks from Focus

Newport’s first guideline on embracing boredom is to take breaks from focus rather than taking breaks from distraction. He argues that if you schedule the exact times you can use the internet and keep all other time internet-free, you will train your resistance to distraction since the option will simply not be there.

Do Nothing But Work for a Set Time

Newport’s next guideline is to allocate the time in your day to focused work. He models this guideline on Teddy Roosevelt’s method of focus during his time in school: he would spend every minute of spare time between 8 am- 4 pm on getting work done so he could have time to relax and participate in school organizations. Newport suggests that you can set a personal deadline for a project to force more intensity during you work time.

Practice Productive Meditation

The final guideline Newport gives that I will be exploring is to “meditate productively.” This involves taking any time you are physically occupied (walking, jogging, swimming, showering, or driving) to focus on a single well-defined problem. Newport gives three steps to productive meditation: review the variables of the problem, define the “next step” question, then consolidate your solution in a clear statement. Not only does this act allow you to use otherwise unoccupied mental time, but it train yourself to resist distraction and remain focused.

I was particularly drawn in by this idea of “productive meditation”. I have jobs all over the state which means that every week I spend upwards of seven hours in a car. I wanted to see how other productive people used their time on the road, so I read the Forbes article Make The Most Of Your Commute With These Eight Productive Tasks by eight young entrepreneurs. Their suggestions were insightful and actually connected to quite a few of Newport’s ideas.

“Record Your Thoughts.” Shawn Porat uses his time in the car to let his mind wander and record any interesting thoughts using a voice assistant. While this is not as intense as productive meditation, in my previous post I shared the benefits of boredom and how taking a break from stimulation can let you have good and interesting thoughts. I know for a fact that I have had some thoughts while sitting in traffic that I wish I had not let dissipate – from now on I will keep a journal in the notes app on my phone.

“Listen to Audio Books.” Robert De Los Santos suggests you listen to audio books on your commute so that you can prepare your mind for critical thinking you will have to do at work. For the past six months this has been my default driving activity – I have been able to listen to twenty books since May, which is incredible considering I had not opened a book for leisure since middle school. If you think this option isn’t for you due to the price (Audible is actually quite expensive) I suggest seeing what resources are available to you from you public library. I was able to listen to all twenty books for free using the app Libby – all I had to do was connect my library card and put the books on hold.

“Do High-level Strategy Work.” Fred Lam suggests you spend the time to plan out your day’s goals for yourself and you company since “without strategy, there will never be execution”. This is more in line with Newport’s productive meditation, but on a daily level. I would do this method, but lately I have gotten in the habit of doing this before my commute with my morning coffee and breakfast.

“Catch Up On the Little Things.” Stephanie Vermaas gives a tip to those who take the train or bus – use this spare time to catch up on emails, phone calls, or to get up to date on projects you are working on. This could be a good time for communication so that when you get to work you can turn it off and not have to worry about checking your email until later in the day.

“Conduct a Daily Review.” Shu Saito utilizes his morning commute by planning out his day, making sure that the most important tasks are at the top of your to-do list. He then spends the rest of his time letting his mind wander, using the silence to perhaps “wander onto a brilliant idea that could recharge your day or business.” This is when your voice assistant would come in handy.

“Listen to Music.” Jared Atchison does what is perhaps on of the most popular options – simply turning up the volume on some tunes that will let you have time to relax or set the mood for your day. I would go a bit further an create some playlists depending on the tasks that you are on your way to conquer to get you ready to face the day.

“Immerse Yourself in Industry-Related Materials.” Derek Robinson strays a bit from boredom by using his commute to get up-to-date on what is going on in your industry through podcasts, webinars, or audio books. While this is not quite what Newport had in mind for “embracing boredom,” it is useful for people like me who have very little time to explore these topics otherwise. Some of the audio books I have listened to were not necessarily industry-related, but work on some of the long-term goals and habits I have in mind for myself. Marie Kondo’s The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up and Dave Ramsey’s The Total Money Makeover have already made an impact on my daily habits – something I argue you should focus on in another post.

Pause and Self-Reflect. Kevin Yamazaki gives the final tip for utilizing your commute that is the opposite of the last tip – avoid burnout by cutting off your work and using the time to reflect on your well-being and current conflicts that could be resolved in your life. He says, after all, “you are the driver for every project you push forward,” so you must take time to think of and take care of YOU.

It is okay to step away from work every once and a while – it is in fact quite beneficial. Train yourself to be used to boredom again so that you can use it to improve your quality of work and life. There is truly no good reason for you to be connected at all times; instead, take some time to connect back to yourself.

-

We all know that deep work is important and does nothing but good for us – but when it comes down to actually doing it, where do we start?

In Cal Newport’s Deep Work, he gives some guidance on how to make the magic of “deep work” happen through a set of rules. The first rule being, of course, to “work deeply”. More specifically, the first rule is to add routines and rituals to your life that make the transition into focus easier.

Determine a Depth Philosophy

The first step in this process is to “decide on your depth philosophy”. Depending on the person and the type of work, their philosophy and approach to deep work will vary greatly.

There are those who may follow the monastic philosophy where they radically minimize or fully eliminate “shallow distractions” so they can focus on work. This could be through only allowing communication via post mail or not allowing outside contact at all in the aim to focus on a clear, discrete, and individualized contribution to the world.

For those who cannot simply cut off all contact from the world the bimodal philosophy may work better. In the bimodal approach, you make those eliminations only in periods of time (a minimum of one day) where you are focusing on deep work. Scholars such a psychologist Carl Jung and professor Adam Grant use this philosophy, benefiting from both long periods of focused time and for “shallow” tasks outside of their typical work.

A more practical approach for the everyday worker is the rhythmic philosophy where deep work becomes more of a habit than an intense session. Comics like Jerry Seinfeld and scholars like Brian Chappell use this method of blocking off a set time in their day to focus only on their work in order to make time for everything else in their lives more worry-free.

The final approach is the journalistic philosophy, where you use whatever free time you can find to work deeply. This one should be practiced with caution, however, as it requires you to be confident in your ability to easily switch into a deep work mindset.

While I would like to say I am confident in my ability to focus, I simply can not. So, I am choosing to use the rhythmic philosophy – I will simply block out a few specific times in my week where I will wake up earlier to get work done…but it is not quite that simple.

Ritualize Deep Work

You have already determined your depth philosophy, so now it is time to go deeper. Deep work must become a strict ritual so that you can make the most of the time you have allotted for focus. Newport suggests addressing the environment, parameters, and supplements for your work.

The environment you work in is wildly important to your focus – if you can dedicate a spot to only deep work that is even better. In addition to location, the time must be set in stone as well. The more specific, the more likely you are to actually follow through. In the Behavioral Scientist article Remedies for the Distracted Mind, it is established that the best work spaces are those that avoid distraction – using only a simple screen and everything not relevant off your desk.

The next step is to define how you will work once you actually start working. Structure is key – know if you what resources you need for the work you are doing and ban/ignore all else. Don’t let shallow distractions like email and instant messaging let you think you are doing work – they are in fact quite harmful to your productivity.

The Behavioral Scientist article actually states that it may take up to 30 minutes to regain focus after checking one of these shallow distractions. Not only that, but it references a study where 124 adults were divided into two groups: one was told to check their email as often as they could and the other was told only to check their email three times a day. After a week the groups switched tasks and it was found that when the subjects were only checking email three times a day, they had “reported less stress, which predicted better overall well-being on a range of psychological and physical dimensions.”

Something that the article suggests you do to put yourself on the right track for blocking out these distractions is using an app like Stay Focused to block or put a time limit on any application on your phone (or your phone in general) during certain periods in the day. I have started to use the app myself and found that it is not only useful in making me stay focused while doing deep work, but that it makes me more aware of how much time I spend on each app.

Divide the “What” and “How”

Now that everything has been prepared for us to dive into actually doing it. We know what we must do, but how should we do it? Newport suggests you execute your deep work “like a business” by following the four disciplines that highly successful companies use as outlined in the book The 4 Disciplines of Execution.

The first discipline is to focus only on “the wildly important” – you must have a specific goal for each deep work session. As the authors of the book say, “The more you try to do, the less you actually accomplish.” Having a single tangible, executable goal not only means that you are more likely to get it done, but that when it is done you will be boosted by the accomplishment you feel having done it.

The second discipline is to “act on lead measures.” There are two types of measures: lag measures, which are what you are ultimately trying to improve, and lead measures, which are smaller behaviors that will support those lag measures. In the case of deep work, Newport suggests, the primary lead measure is the amount of time spent in deep work.

The third discipline is to “keep a compelling scoreboard.” Newport’s scoreboard of choice is a row of paper with a tally marked for each hour spent working deeply, the hours where he achieved a goal or finished a task being circled. Any sort of visual representation works – choose something that displays your “score” (hours spent in deep work) in an exciting and energizing way.

The last discipline is to “create a cadence of accountability.” This can be in the form of weekly meetings to share progress (which pressures you to show that there has been some) or planning your week ahead of time. My personal choice is to use a whiteboard in my room with a checklist of the major tasks I have to get done on each day, along with a portable checklist in my planner. Nothing is more satisfying than checking off all the boxes in a large list!

Cut off the Stimulation

The final step to doing deep work is to stop doing it. In fact, it is best to stop doing anything related to work at all. At the end of your deep work, shut down all thinking and all work-related communication.

Having downtime aids in creating insights we night otherwise never let ourselves reach. In the TED Talk How to Get Your Brain to Focus, Chris Bailey makes the conclusion that due to all this screen time and constant communication, our brains are over stimulated which makes focusing difficult. He says that we are victim to our brain’s novelty bias – the crave for dopamine release that ends up taking over all of our time to actually take a breath and think.

After doing research on focus, Bailey did a month-long experiment where he did a “boring” task for one hour every day from reading the terms and conditions to staring at the ceiling. What he found was that after a week, he adapted to this “under”stimulation and during these times great ideas and plans came to him simply because he let his mind wander. He concluded with the thought that we should re-discover boredom because distractions are not really the enemy – they are a symptom of over-stimulation.

In addition to allowing time for insights, being lazy lets you recharge your brain so you can be more productive when you are doing focused work. Also, as Newport points out, the majority of the work you would do after-hours is typically not important so you should save your focus for the more constructive tasks.

Now we know how to do deep work, but let’s step back an take a look at the why.

In previous blog posts, I have explored the tremendous effects that smartphones and the technology boom has had on the world and every single person inside. The article A Sociology of the Smartphone brings many of these effects to the forefront by reminiscing on the world before – a world of physical objects like pictures, cameras, keys, tickets, photos, calendars, and maps that we relied on. Now, everything we rely on is all in one device – a device that has become a part, for some a big part, of your identity.

Not only are the things we are reliant on in our phone, but as phones are becoming more and more widespread the option to use anything else is being taken away. This is especially harmful when it comes to sharing our personal data – surrendering our data is no longer becoming a choice, but a necessity. As Adam Greenfield says in his article, “whether we’re quite aware of it or not, we are straightforwardly trading our privacy for convenience.”

Greenfield ends his article with a quote from Winston Churchill: “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” While his application of this quote is to show how we have created this grim situation by creating tools like smartphones and communication networks. While I agree with this take, I think this quote can be used in a more positive and proactive way.

“We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.”

Greenfield, A. (2017, June). A sociology of the smartphone. Longreads. Retrieved from

https://longreads.com/2017/06/13/a-sociology-of-the-smartphone/Even though these buildings have been created and we are becoming more aware of the negative effects they have caused, there is no reason that we can’t demolish them and create new buildings. This time, let’s construct the building with our well being, including our ability to focus, in mind.

-

Project management sounds rather intimidating. First of all, there are so many types of project management: Waterfall, Agile, a Hybrid of the two, Design Thinking, Kanban…the list goes on and on. These styles of project management are used by designers to outline what needs to get done and by who in order to reach goals for their products in a set amount of time, considering all constraints and possible setbacks.

According to the Wikipedia article on project management, while there are many types of project management approaches, successful ones typically focus on these four main aspects: the plan, process, people, and power in a given project. It is important to have a clear idea of what resources are available to you and how you should allocate all of your resources to be the most effective it can be.

With those aspects in mind, a project continues on to begin its process groups: initiation, planning, executing, monitoring, and closing. In initiation, the scope, costs, and schedule must be defined.

According to the video Project Planning Process: 5 Steps To Project Management Planning the planning process itself is broken down into five steps: creating the plan (they suggest using templates) to mobilize the project, breaking down deliverables and receiving as much input as possible about them, determining dependencies and potential risks/issues, creating a solid timeline, and assigning resources to the project.

In executing, you simply follow the plan that was constructed in the last step. At the same time, you are monitoring and controlling the project – you should be asking “where we are”, “where we should be”, and “how we can get on track again” then implementing what resources you can to improve the process.

Now that the project management process itself is a bit less intimidating, how can I apply this to my life as a student? The farthest I have gone in “managing” my deliverables is by using myHomework. While it has proven to work for me in the past (all the way back to freshman year of high school), my projects are becoming more complex and include multiple steps that need something a bit more visual and organized than a simple list.

While it will be sad to let go of myHomework, I need something a little less linear. As my projects are growing, I am in need of a program that goes beyond “incomplete” and “complete”. I needed to explore more applications that make sense for me to use as a graduate student and a filmmaker. I decided to go with Trello as it allows me to meet all of my organizational needs – I can create boards for each subject, change the lists to match the needs of each project, and create sub-lists for multi-step projects.

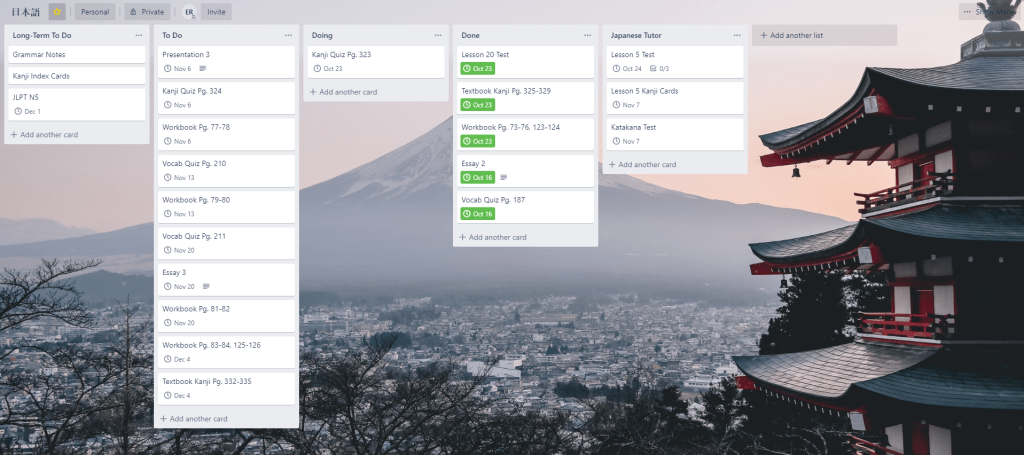

For more linear projects, I chose to go with the Kanban method for my lists: To-do, Doing, and Done. As you can see I also added “long-term to-do” for things that are longer-term goals and a list for my weekly tutoring sessions. Since it is so easy to create the cards, I went through my syllabus and added the rest of the assignments for the semester to the “To-Do” list- I will simply drag the cards over to “Doing” once they are assigned in class.

While the simple style of myHomework works well for classes like Japanese, isn’t this so much more appealing to the eye? What is wonderful about Trello’s versatility is that it also suits my needs for film projects. In Matt Jacobs’ article How To Use Trello for Video Production Project Management he highlights Trello’s collaboration feature and explains how to use tags to assign each task to a specific person. It is also useful that you can set deadlines for specific tasks – deadlines are important in filmmaking and there are many to keep track of.

Instead of using Kanban, I separated the lists by the different phases of production. In Jacobs’ article, he talks about how editor Zach Arnold (known for his work on Glee and Burn Notice) converted to Trello from his old method of using index cards and post-it notes for his projects. Arnold uses Trello to its full potential by adding members, paperwork, a workflow checklist, and due dates to each task.

I added all of this important info: members, paperwork, a checklist, and the due date. I even shared my Trello board with the other members in my group. Even though we meet twice a week, there is always someone asking for clarification about a due date or who is doing what or where a specific document is. Now, we simply have to remind each other to check the Trello board.

While I have found project management to be very useful in my school and work life, I felt like I was lacking in the project I am constantly trying to work on: myself. After viewing the video Work Smarter Not Harder, I realized that I need to focus more on the “why?”: I need to define the results I want from doing everything I do in order to improve not only my quality of work, but my life balance.

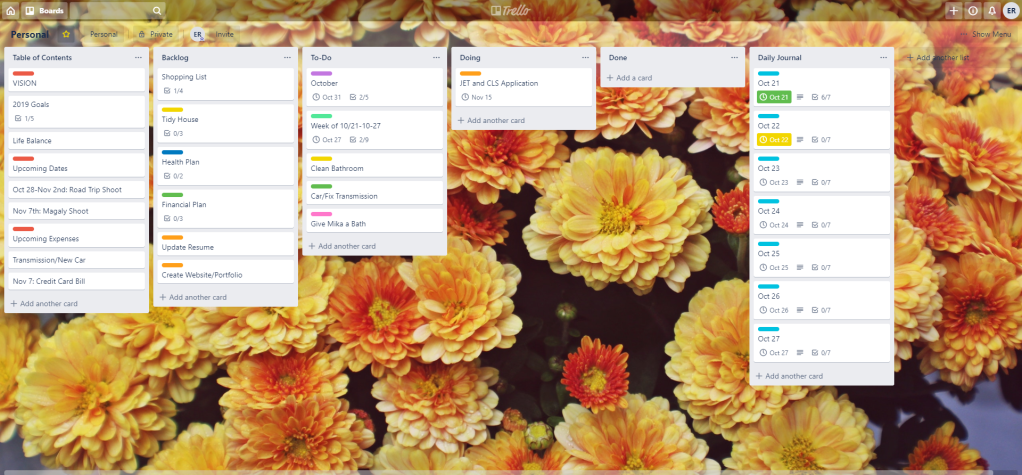

My first “Personal” Trello board looked like this. I thought it would be best to separate my lists by each aspect of my life that I wanted to improve upon. However, it somehow ended up looking bleak and overwhelming at the same time.

Then I read Britt Joiner’s article How To Build A Daily Habit Tracker In Trello (And Reach Those Goals!) and sympathized with her statement that she found herself on “auto-pilot” to complete tasks rather than working on long-term goals. She said that to remedy this, instead of simply listing projects, she “builds systems and habits that would hold [her] accountable to my goals along the way.”

This was the end product – much more organized and easy to follow. I go in depth below. She references James Clear’s idea that rather than focusing on your goals, you should focus on the systems you use to reach them. In Clear’s article Forget About Setting Goals. Focus on This Instead. he outlines the four main problems with goal-centered thinking.

First of all, he says that winners and losers share the same goal – it is only the winners who went beyond having a goal by implementing a system to reach it. The second problem is that achieving a goal is only a momentary change. If one instead focused on fixing problems at a “systems-level”, the outcome will automatically improve.

“Fix the inputs and the outputs will fix themselves.”

Clear, J. (2018, October 16). Forget about setting goals, focus on this instead. Rockyhouse

Publishing. Retrieved from https://jamesclear.com/goals-systemsThe third problem is that by setting a goal you are restricting your happiness, or rather you are saving your happiness for your future self who completed that goal. To solve this, we must not look at the binary system of goals (either reaching it or not) and focus on the system we can make to better ourselves.

The final problem with goals is that they are contradictory to long-term progress, since when we reach a goal we typically stop doing the good habits that lead to its achievement. Clear argues that our aim should be to “continue playing the game rather than winning it.”

With system-centered thinking in mind, I set out to follow Britt Joiner’s template for a habit tracker that would not only help me reach my goals, but improve my happiness for my present self.

First she suggests setting the building blocks by creating a table of contents with the overall vision and themes for the year, upcoming dates, and upcoming expenses. This is an at-a-glance reminder of why I am doing these daily habits.

Next, she suggests mapping out goals and projects with the “backlog”. However, since balance is the real goal, theses projects must be a priority or fit into the yearly goals.

Then she says we can “make the magic happen” in our “To-Do” list. She suggested creating a monthly and weekly card for the habits you want to keep repeating. The monthly list should include small actions that lead to larger goals and the weekly tasks should be smaller habits that you can look at and get done in a few minutes.

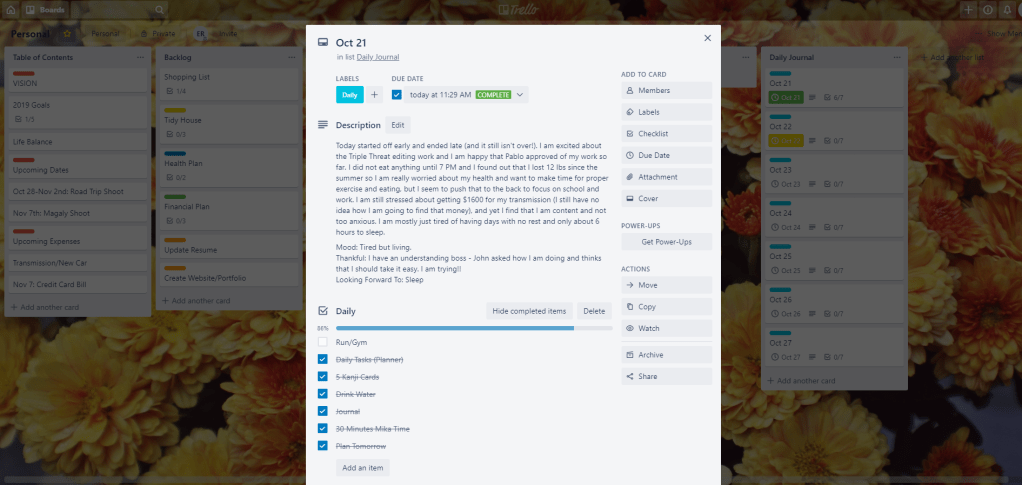

Finally, there is the “Daily Journal” list to promote creating the right daily habits. This list has a card for each day that includes a daily journal, some quick check-in questions (I chose mood, thankful, and look forward to), and a daily checklist.

I hope to create a similar board for my work life once I begin a daily office job following the habits suggested in the video 7 Work Habits You Need to Succeed – Project Management Training. For now, though, I need to hold myself accountable to improve my health and decrease my stress. By mobilizing my project plan to improve myself, I think I am heading in the right direction.

-

I have an addiction.

This week’s assignment for class was to give up some sort of distraction in our lives – do a “digital detox”. Knowing that YouTube is my main source of entertainment (and procrastination) I decided to give it up for seven days. I did not realize how much of a distraction it was until the first day of my detox when I decided to look at my YouTube history for the previous week and calculate the total minutes watched.

It came out to 1549 minutes. That is over a day of time spent on YouTube! While I was sick and in bed for a few of those days, even the days I was healthy I was spending up to three hours watching videos that, as I came to realize when studying my history, where not particularly interesting.

This addiction is not something that I am alone in. In Domingo Cullen’s article YouTube Addiction: Binge Watching Videos Became My ‘Drug of Choice’ he talks about how a simple bad habit of watching YouTube videos for a good chunk of his weekend turned into an all-out addiction that affected his work and social life. He found that watching these videos did not even bring him joy or “improve his life in any way,” but simply served as something to do in a world that encourages doing things constantly.

“To be addicted it to be completely at the whim of your impulses.”

Cullen, D. (2019, May 3). YouTube addiction: binge watching videos became my ‘drug of

choice’. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/03/youtube-addiction-mental-healthLike Cullen, I used YouTube out of habit – the second I felt any sort of silence or boredom, I quickly settled for a video that would at least serve as background noise. I was not doing this action deliberately, rather as a wanton who is afraid to slow down and face the silence.

It is unfortunate that this is how I handle such a useful tool, since there can be much to learn from digital content. Hossein Derakhshan’s article The Web We Have to Save outlines a major shift that has happened in the way the internet is used and how we consume information. He found that after being away from the internet for six years he had to completely change his approach to how he wrote and presented himself to be at all relevant in today’s social-media centrist internet. He could no long simply write and share information, he had to give in to the norm of today’s media standards by being active on social media and giving into the “stream” that controls what every single person on the internet sees. Most disturbingly, he found that we are departing from a book-based internet to a television-based one.

There is of course nothing wring with (a healthy amount of) television, but when the line between information and entertainment is that blurred, dangerous things can happen. In my case, I am misusing YouTube in both an educational and entertainment-filled aspect. Since I am typically watching videos because it is simply something to fill the silence, I do not deliberately seek it out for quality entertainment or for valuable information.

One case of a video that I did end up watching with purpose was Matt D’Avella’s 4 Rules for Digital Minimalism. In this video he did a seven-day detox that followed four rules: (1) no screens in bed, (2) all email once daily, (3) social media limited to 30 minutes a day, and (4) limit all streaming to one day. During this experiment, he found himself in a state of discomfort without access to passive entertainment. He had to get creative with how he spent his time and would sometimes simply have to spend his time doing nothing. However, he found that he was much more productive with his work and was glad to experience the nothingness that many of us miss out on in modern life.

Funny enough, this video was an example of our week’s assignment. Inspired by one of my favorite content creator’s video and in the hopes of finding some sort of explanation for my feeling of constant overwhelm by work and school, I decided to go into the depths of discomfort. I would quit YouTube, Reddit, and using my phone in bed at all.

Coming out of this experiment, I felt enlightened. What was most shocking of all was that when I started watching YouTube again, I found that I did not really miss it. I have no desire to watch or listen to videos as I am trying to do other work. I am now comfortable with the silence and realize I will only be distracted and not gain anything by watching. With my use of YouTube in the future, I will be much more deliberate to not only make more time in my schedule, but to make the act of giving attention to it more special. In doing so, it will make the attention I gave all of my work more special too.

In Chapter Three of Cal Newport’s Deep Work, he discusses how science writer Winifred Gallagher discovered how to live her best life after being diagnosed with late-stage cancer: she simply chooses to pay attention to what really matters to her and makes her happy rather than dwelling on things she cannot know or control.

I often find myself doing exactly the opposite: I am always thinking about what I could be doing, how I could be improving, what I am doing wrong. In these times, I get stressed. During my detox when I was stressed was when I missed my access to mindless entertainment most. I use it as my distraction – I am not choosing to watch videos or scroll on my phone because I think it will improve my life, I am doing it because I do not know how to manage my thoughts when my thoughts are all that is there.

“‘The idle mind is the devil’s workshop’…when you lose focus, your mind tends to fix on what could be wrong with your life instead of what’s right.”

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work (pp. 82). London: Piatkus.That is why I have created rules for myself going onward – I want to force myself to have those uncomfortable silences and to do each action with more meaning and attention to it so that I can appreciate it for what it is. While I feel overwhelmed by school and work, I actually love doing both. If I can simply spend more time paying attention to what I am doing instead of fearing for what is next, I know that I will feel better like I did during my detox week. I will do my best to overcome my addiction.

Unfortunately, my addiction is something that is not-so-strange for many people in my generation who have access to the internet constantly. As Cullen points out in his article, eating addictions are difficult because “the lion is let out of its cage” three times a day, but “when most of our time is spent looking at screens, internet addiction means the lion never has a cage to begin with.”

This large amount of time looking at our screens has proven to be detrimental to my generation in a multitude of ways. In the article Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation, Jean Twenge lays out data that points to concerning trends. Those in younger generations who use their smartphone more than the average amount of time are lonelier, unhappier, and more mentally unhealthy. Kids are much more dependent and childhood has extended well into high school, with the rates of teens driving, having part-time jobs, and dating going down rapidly since the 90’s.

While I did have a part-time job, drive, and dated in high school, I felt and still feel like I do not have enough time for everything because I spend so much of it on mindless entertainment. When there is so much stuff filling up my time and my use of the internet on top of that, I feel like I am drowning.

I also relate to those teens Twenge discusses who do not get enough sleep at night. In an the article Why Electronics May Stimulate You Before Bed, the National Sleep Foundation outlines that the use of electronics before bed delays the body’s internal clock, suppresses the release of the sleep hormone melatonin, and makes it more difficult to fall asleep due to the short-wavelength blue light that electronics emanate. This is troubling because this causes a delay for the onset of REM sleep and reduces the overall amount of REM sleep a person gets which can lead to a chronic sleep deficiency.

This may be why when I did my detox and read instead of using my phone in bed before sleeping I had vivid dreams almost every night and my sleep quality raised by a small but significant amount. I also woke up feeling more rested, and in turn started the day more optimistic and energetic. Because of these changes I experienced in that week, I will continue to ban in-bed phone use for myself.

It will be hard to un-do these habits that I have been doing ever since I bought my first iPod touch in eighth grade, but going cold turkey was made me realize how truly beneficial can be. I also want to be a person who acts on what they preach – when I have children, I will limit their screen time in an attempt to avoid the negative side effects outlined in Twenge’s article. If I am unable to limit my own screen time as an adult, how can I force my kids to?

I am tired of giving into the whims of my impulses. I am tired of being unfocused. I am ready to be more deliberate with my actions so that I can live a better and less distracted life.

-

Our brains are hacked. In an age where information is more accessible than ever, we are conditioned by the tools we use to set aside our free will for that wonderful feeling we get when we get a text, give a like, and continue to scroll. This conditioning has been proven to cause a multitude of detrimental effects on our lives and work, and yet we keep feeding into our addictions and the tech companies we got our addictions from refuse to make change.

How did this happen? Why is nothing being done to stop this? Is there even a way to stop this?

Short answer: yes. Longer answer: yes, but it will require us to re-wire ourselves to tolerate doing hard work.

In Chapter Two of Cal Newport’s book Deep Work he argues the business trends like open offices, instant messaging, live collaboration, and a social media presences that are pushed onto workers and praised as good practice are, in fact, damaging our ability to do deep work and retain focus.

It’s bad enough that so many of these trends are prioritized ahead of deep work, but to add insult to injury, many of these trends actively decrease one’s ability to go deep.

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work. London: Piatkus. pp. 51A study done by Gloria Mark covered in Episode Seven of Pardon the Interruptions found that when a person stopped what they were doing to check an email (those of whom where in the higher percentile checked it 435 time in a single day) it takes a significant amount of time to regain focus and get back on track with the original task. In another study of hers, she had her subjects turn off their email for a whole week and found that their focus levels rose and their stress levels decreased significantly.

She was not the only one to do a study to explore the effects of multitasking. In a 2013 study on 319 undergraduate students it was found that not only does multitasking effect a person’s ability to filter out irrelevant information and ignore distractions, but many of the subjects reported symptoms associated with anxiety and depression.

Even with these studies and so many more like them that prove the negative effects of multitasking and being always-available, businesses keep promoting this behavior (and often give punishment if it is not done) and we keep feeding into it.

Newport suggests that this embrace of new trends is an explicit example of Neil Postman’s idea of an internet-centric technopoly that was created in the 90’s: the idea that if something is high tech, that it is automatically good, so people and businesses will use it and eliminate other alternatives to it so that its use is simply not up for discussion.

Not only do we have the pressure from businesses and the cultural push towards tech, but we often follow the principle of least resistance. Newport argues that when we are working we will tend towards tasks that are the easiest to do in the current moment. This tendency means that in an environment where email and communication is seen as productive, it is perfectly acceptable to only spend time on communication, leaving little room for the deep work where quality comes from.

This idea is not exclusive to a work setting. Our entire lives are controlled by our communication via social networking. In the CBS 60 Minutes piece “What is ‘Brain Hacking?’” Tristan Harris, a former Google product manager, declares that your phone is a slot machine. Designers of apps create features and functions that have the sole purpose of making you want to use it more. He calls this type of developing “a race to the bottom of the brain stem” since these functions are simply taking advantage of user’s implicit emotions.

In the article “‘Our Minds Can Be Hijacked’: The Tech Insiders Who Fear a Smartphone Dystopia” Justin Rosenstein, the creator of the “like” button, shares how he does not use social media anymore just for that reason. He says that the addiction of constantly checking for notifications and being connected is causing us to have “continuous partial attention” and limiting focus and potentially IQ. He is particularly concerned for the future.

One reason I think it is particularly important for us to talk about this now is that we may be the last generation that can remember life before.

Lewis, P. (2017, October 6). ‘Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a

smartphone dystopia. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/oct/05/smartphone-addiction-silicon-valley-dystopiaIt is becoming the case that only a handful of tech companies are the entities attempting to control every aspect of our lives. In Franklin Foer’s article “How Silicon Valley is Erasing Your Individuality” he discusses how these companies are not only in a race to become everyone’s “personal assistant”, but that they are against free will by using algorithms to “automate the choices, both large and small, we make as we float through the day.”

And we are letting it happen. Society is stuck in this mindset that all things new and technologically advanced must be good. The idea that instant communication and technology allows us to get more done in the day is true (think of all the emails that can be sent in a day!), but the quality of work is going downhill and deep work is becoming more and more rare.

Foer uses the analogy of processed foods. When they were first invented, TV dinners were the best – you could cook a yummy meal in no time! Processed foods became the norm since they were so efficient and cost-convenient, and here we are now in a country that is addicted to sugar and riddled with diabetes and obesity.

While it is probably impossible to stop the tech companies from using techniques to get you to come back since that is how they make their money, you can be more aware. Follow the steps of those tech insiders that don’t get high on their own supply. Use technology diligently and with purpose. Set boundaries for your communications. While it will require you to take the path of more resistance, the outcome will be better not only for your work, but for your well being.

-

Deep work. It sounds easy enough, right? I just have to set some time aside to get this project done and go to the library so I can focus on only the task on hand. I’ve done it time and time again, project after project – usually the night or day before it is due (“working under pressure makes diamonds,” I would tell myself).

I mean, it works – I have yet to get an unsatisfactory grade and I get A’s in all my classes. And yet, I feel like I can do better. I can do more. I can work deeper.

If there is anything I have learned from producing video content, it’s that you only improve if you produce. The more you make, the more you learn. And here I am, about to graduate with my bachelors, and having only one (what I would now consider mediocre) documentary to my name. I can do better.

Now I read Cal Newport’s Deep Work and I know I can do better. If I could be one of those top performers who masters new skills fast and produces quality work in a short amount of time, I really can be on top. And I know I can do this. I know I can do more.

But how?

I work three part time jobs, take five classes at school, participate in several school clubs, have a dog to take care of, and freelance projects to work on. I often leave my house at 9 and don’t return until 10. This is not something that is new to me, but it leaves very little wiggle room. How can I find time to work deeply if I have barely any time at all?

Laura Vanderkam’s article How To Make Time For Deep Work When Your Calendar Is Packed With Meetings not only gave me some tips on how to find the time for deep work, but gave me a realization: in order to do my best work consistently, I have to set solid rules for myself.

The Rules

Don’t Have Time? Make Some. Sounds harder said than done. But think about it – how many times a week do you make time for friends, family, or colleges? Scheduling meetings for them is not such a big deal, so schedule some time for yourself. As Vanderkam says in her article, “making time not look open is often key to protecting it for solo work.”

Start out small, only 2-3 blocks of time a week. If you don’t have time during the week, make time in the mornings or on the weekends before your normal activities would start. Yeah, getting up early can suck, but starting the day having accomplished good work makes it worth it (and allows you to relax during you relaxation time).

Put the Phone Away. Far Away. There are countless studies showing the negative impacts that having a phone in you immediate proximity is detrimental to your focus. One of these studies by The Harvard Business Review found that the further away a person was from their phone, the better they were are preforming cognitive tasks. Subjects whose phones were in front of them during those tasks actually preformed just as poorly as those who were sleep deprived – which, admit it or not, you often are in college. Talk about a double whammy!

Remember Those Solo Meetings You Made? Use One of Those to Read. The last time I sat down to read a book on my own accord was… if I am being honest, I actually can’t remember. Don’t get me wrong, I love books. During my grueling 3-4 hour a day commute this last summer I was able to listen to 12 audio books. But when I try to pick up a physical book, I find that I simply cannot read on – unlike in my car where I can only drive and listen, I am using precious time that could be spent working on numerous projects, homework, cleaning…the list goes on forever. While this rule does not directly help you get work done, it does help condition you, or rather re-condition you, to have patience.

I am not the only one. Micheal Harris’ article I Have Forgotten How to Read not only shares his own struggles, but outlines a problem that effects far too many – we have no patience for physical books. He deducts this is due to the fact that he has learned to do “cynical reading” from electronic sources, where we simply look for useful facts then move on to the next thing. He quotes Nicholas Carr, saying “digital technologies are training us to be more conscious of and more antagonistic towards delays of all sorts,” and reading physical books require us to purposefully delay ourselves. When we read physical books, we read with a sense of faith that some larger purpose will be served – and we have lost that faith.

And When You Read, Read Actively. There are some rules to reading that make it not only easier, but more valuable and enjoyable. The article How to Remember What You Read gives you a guide for what to do before, during, and after you read to make to most of the book – and the investment of time you put into it. Some of the most useful pointers seem like common sense, but are ones that I have ignored like only reading what is interesting to me and dropping a book after 50 pages if I have not been hooked.

And, that’s it. Only four rules. I pledge to begin following these rules – now. Not because I have to, but because I want to. Because I can do better. Because I want to do more. Because I can work deeper.