“A Picture Says A Thousand Words.” – This is a phrase that you have no doubt heard before. Words are great at conveying information, of course, but cannot match the power of a visual when it comes to telling a story. The raw, tactile emotions that can be conveyed by a single image allow for people to understand situations much quicker, and with more empathy. While there are difficulties in capturing documentary photographs the images wield power that words are unable to.

The birth of photojournalism is often attributed to the photographers like Alexander Gardner and Mathew Brady who captured images of the Civil War. Historian Mark Katz explained that they were able to make the tremendous accomplishment of “extending the power of the photographic image [to] affect public awareness. The photographic coverage of the Civil War by Gardner and others sent authentic images of the horrors of the battlefield directly to the public for the first time” (Harris). For the first time, a conflict was able to be experienced by those who were not at the scene.

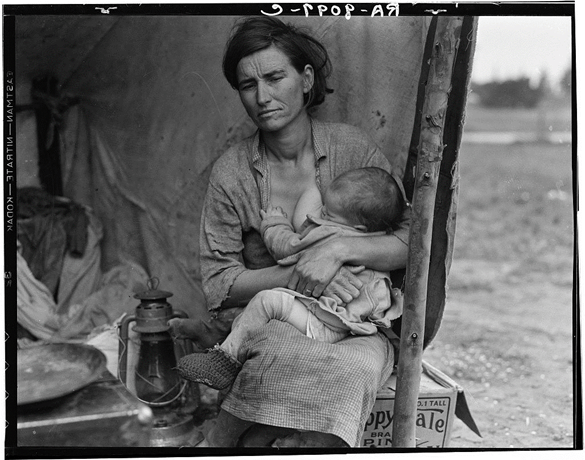

Another wave of photojournalists arrived when depression-era photographers were funded by the government to promote Roosevelt’s New Deal. One of the most influential photographers of the time was Dorthea Lange. Historian Linda Gordon argues that her work was an outstanding display of democracy, writing that “By showing her subjects as worthier than their conditions, she called attention to the incompleteness of American democracy. And by showing her subjects as worthier than their conditions, she simultaneously asserted that greater democracy was possible” (Gordon).

Photos became a tool that allowed us to tap into people’s lives and cultures, whether they are a thousand miles away or our neighbors. Photos are not filtered through a writer’s words – rather, documentary photographers should strive to take each photo to show the reality of the situation. As photojournalist Tom Rankin said in his introduction to the Southern Cultures journal, “we strive with all we have to make full representations of what sits in front of and around us, trying to make something lasting and true that will bring us back once again to reflect–again, again, and again–on just what transpired, what it all means“ (Rankin). This image that he took on the side of the road after helping jump-start a young couple’s car in Alabama paints a picture that has many implications – they mean something completely different to people from different parts of the country and with differing political views. The important thing is that as he took the photo he intended for it to simply be the moment, not to put any agenda behind it – that is up to the viewer to decide.

There are some images, however, that convey emotions so strongly that almost every person who views them can empathize with the issues of the subject. When context or action is added to the image, the result is an encapsulation of “the moment”. This combination of action and emotion that photojournalists capture tells so much in a single shot (Gitner). Take this image, for instance. A young man at bat, just a millisecond away from taking his swing. The nervous but determined expression in his face is something that everyone can relate to. This photo is both authentic and sensory – it is full of an emotion that is difficult to capture in words, but easy to understand by the look of a person’s eyes (Lien).

Some argue that this “moment” is at times fabricated by photographers to create a more dramatic and interesting scene. Unfortunately, this is the case for more than half of the news photographers in the United States who say that they sometimes stage photos and for the 12% that say they stage photos half of the time (The New York Times). Not only does this go against most codes of conduct for the agencies that they work for, but it makes moments less reliable in the public eye.

Not all staging is inherently bad, however. Take portrait photography for example – the goal of this type of photograph is to give a representation of a person (or more often a group of people) through a single image. Migrant Mother by Dorthea Lange is perhaps the most famous photo portrait in existence, and the topic of hot debate as to whether Lange directed some elements of the photo or not. In an analysis of the photo series on Jorg Colberg’s Conscientious Photo Magazine he argues that “Portraiture makes the viewer’s task particularly tricky, because it often seduces us to see things that aren’t actually there. A photograph of another person never is that other person. It always ‘only’ is a photograph, made with specific devices and (usually) intent” (Colberg). This is necessary to create a photo – after all, a photographer cannot include every element of a person into one frame.

Still, is necessary for the viewer to think about what is in the image, and more importantly, what is not. In the case of Migrant Mother, the daughter of the mother herself reflected on why her mother came to dislike the photo. “She was a very strong woman. She was a leader. I think that’s one of the reasons she resented the photo—because it didn’t show her in that light” (Library of Congress). Even though the series of images painted a portrait of the struggles of the impoverished American people, it was not necessarily representative of the subject herself – that was what was not in the image.

Alexander Gartner, the Civil War Photographer mentioned earlier, staged to a more direct degree. He would move dead bodies to create a better composition and even went as far as to dress the same dead body in both Union and Confederate uniforms to push the idea that the Civil war was causing mass destruction and loss on both sides (Curto). This sounds terrible to a person who hears it at first, but considering the limitations that Gartner was facing it is important to consider if he would have had the same impact on the American public had he not staged some of the elements. The intention was well placed and he made a significant impact on the way Americans viewed the war – but by modern standards what he did would be highly immoral.

Intention of the photographer is important not just for the viewers of the image to consider, but it distinguishes documentary photography from photojournalism. There are many similarities between the two, but professionals in photography such as Rebecca Nasr find the difference in intention (Gautreu):

Though [documentary photography] is close to photo-reporting or indeed press photography in general by virtue of both theme and, on occasion, plastic form, it remains distinct from them… Its characteristics are, on the one hand, a discourse, an intention, a positioning on the part of the author and, on the other hand, a relationship between photographer and subject that involves a time-scale.

Gautreau

This distinction has become more blurred in modern times. Now that visuals are a core element to most stories – as Mario Garcia puts it the written and visual part of a news story is “now a single until of thought” – photojournalists strive to follow the same techniques as documentary photographers (Garcia). The difficulty of not only gaining the trust of a subject, but maintaining it, is especially important since the trust in media is so low. John Happel of Nieman Storyboard observed that “thinking about access in ways that extend beyond the superficial is important not only in terms of a storyteller’s craft, but also his or her credibility – and humanity” (Happel). Still, with the time constraints that are inherent in journalism, it is difficult to get that time-dependent relationship between subject and photographer that is necessary for a successful documentary photo.

In addition to this difficulty to connect when there is a looming deadline, there are factors outside of the photographer’s control that could influence the way their subject feels about them, and in turn, how open and authentic they may be. Even with great amounts of time and effort a good relationship may not come into fruition. In a study by the Queensland University of Technology it was found that there were over twenty factors that could influence subject-photographer relations, only two of which the photographer has complete control over (Thomson).

There are not only these roadblocks, but the aftermath of working as a photojournalist in a world that craves bad news. On the BBC News website, 19 of the 20 most clicked stories in 2015 were negative (Campbell). There have been many studies on the detrimental effects that all this negative news has on the reader, but recent surveys show that up to 98% of photojournalists have been exposed to traumatic events and almost 6% could qualify for a PTSD diagnosis (Thompson). While this may not have been brought to many people’s attention, it makes sense after realizing how many horrific images of starving, injured, or dying people, wars in action, wreckage from terrible storms, and other depictions of awful situations we are witness to in the news cycle.

The price that journalists pay is unfortunate, but the power that the images they take can do so much good. There are moments in history where change was made or pain was felt – so many of these moments that no one outside of that situation would be aware of if it had not been captured. For instance, it was not only the news that pushed much of the American public to protest the Vietnam War – it was the photo and video evidence that shocked the world. As photojournalist James Nachtwey explained in his TED Talk, “politicians were telling one thing, photographers were telling another” (Nachtwey).

The ability that sharing an image of a human face – a face of a person being affected by otherwise unimaginable conflicts – make those conflicts seem much less far away and abstract (Nachtwey). While words could explain death and destruction, nothing can convey grief like a face full of sorrow. No words can convey pain like the image above.

Single photographs have also been able to represent struggles of an entire population. Take the image below as an example. The man standing in from of the tanks on Tiananmen Square during the 1989 protests and massacre represented the strength of individuals against forces much larger than them. Not only is a photo the capturing of a moment – it is able to be easily reproduced and spread to the world so that these struggles can be understood and change can be made (Memou, p. 1-2).

Even though most photojournalism (and news in general) covers negative events, a rising trend is “solutions journalism” – where the story moves beyond the issues and looks at the efforts to respond to them (Midberry). David Campell, the director of programs and outreach at The World Press Photo Foundation asked, “If you can capture all the problems with a photo, why can’t you capture the solutions?” (Granger) While capturing sadness and anger can spark revolutions and make changes to unjust systems, it is important to not underestimate the power of positive imagery.

A study by Karen McIntyre of Virginia Commonwealth University found that positive news has a significant positive affect on reader’s moods. Even stories about events that are negative can still make the readers feel good by highlighting a positive outcome (McIntyre). The image below is a part of an AP story breaking news of making leeway in getting same-sex marriage legalized back in 2013. Instead of focusing only on the pain and struggles that the LGBTQ community took to get to that point, the article takes a moment to revel in the positivity that came from their hard work by sharing a personal story of a couple that could finally legally be together (The Associated Press).

It is not only photos that have more impact than words, but the person behind the camera. In a study published in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly the images from the Times Hearld-Record were analyzed before and after the layoff of all their photographers. They found that “professionals are better at capturing intimate, emotional, and graphically appealing images than non-professional photographers” and 82% of the images captured by the non-professionals were purely informational (Mortensen). The professional photos also more often included conflict, action, the “human element”, and timeliness than the non-professional photos. While the study was unable to conclude that one form of photography was better than the other it solidified the fact that photojournalists can highlight the human side of an issue (Mortensen).

Now there is a rising population of citizen photojournalists that can capture moments as they happen from the point of view of a person being affected by the experience. The images taken by terrified students during a lockdown or the events of a natural disaster as it is unfolding is difficult to compete with. They are there right as the action is happening, after all. Still, the ability to represent a person’s struggles in a way that is approachable and effective is strong in professional photojournalism. An analysis of these two sources of photojournalism by Stuart Allan suggests that instead of choosing to endorse one or the other, collaboration between the two can bolster a story’s facts and emotions even further (Allan). Both of the images below (the top done by a professional, the bottom by a citizen) are valuable by themselves, but together they help pain a more complete picture.

Photojournalism and documentary photography create a human connection. Everyone has the same ability to harness and express emotions, so when those emotions are shared through visual proof the world comes closer together and change can be made.

Works Cited

Allan, Stuart. “Introduction: Photojournalism and citizen journalism.” Journalism Practice, vol. 9, no. 4, pg. 455-464, DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2015.1030131.

The Associated Press. “Supreme Court issues landmark gay marriage rulings.” The Associated Press, 26 June 2013, https://www.peninsuladailynews.com/news/breaking-news-supreme-court-issues-landmark-gay-marriage-rulings/.

Campbell, David. “Why it’s time for visual journalism to include a solutions focus.” Medium, 22 Jan. 2018, https://witness.worldpressphoto.org/why-it-is-time-for-visual-journalism-to-include-a-solutions-focus-5be15aec3afc. (Module 4)

Colberg, Jorg M. “Looking at Dorthea Lange’s Migrant Mother.” Conscientious Photography Magazine, 20 May 2013. https://cphmag.com/migrant-mother/. (Module 7)

Curto, Jeff. “Photo History Class 2: History Survey Part 1.” History of Photography Podcast, 24 Jan. 2014, http://photohistory.jeffcurto.com/wp-content/podcasts/Photo_History-Class_02_Podcast_Survey1.mp4.

Garcia, Mario R. “Digital storytelling, Part One: The fusion of writing/editing/design.” Garcia Media, 19 Jan. 2017, https://garciamedia.com/blog/digital_storytelling_part_one_the_fusion_of_writing_editing_design/. (Module 4)

Gautreu, Marion & Kempf, Jean. “Contemporary documentary photography in the Americas.” IdeAs, vol. 13, 1 March 2019, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ideas.5542.

Gitner, Seth. Multimedia Storytelling for Digital Communicators in a Multiplatform World. New York, Routledge, 2016. (Module 1)

Gordon, Linda. “Dorthea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits.” W.W. Norton & Co. Inc., New York, 2009.

Granger, Jacob. “Solutions photojournalism.” Mousetrap Media Ltd, 28 Aug. 2019,

https://www.journalism.co.uk/news/solutions-journalism-meets-photojournalism-responding-to-community-problems-with-a-camera/s2/a743828/.

Happel, John. “Five immersive photographers share their experiences on gaining trust.” Nieman Storyboard, 19 April 2018, https://niemanstoryboard.org/stories/five-immersive-photographers-share-their-experiences-on-gaining-trust/.

Harris, John M. ““Truthful as the Record of Heaven”: The Battle of Antietam and the Birth of Photojournalism.” Southern Cultures, vol. 19 no. 3, 2013, p. 79-94. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/scu.2013.0021.

The Library of Congress. “Exploring Contexts: Migrant Mother.” American Memory, https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/awhhtml/awpnp6/migrant_mother.html.

Lien, Jade. “The Four Principles of Visual Storytelling.” Action, 21 Dec. 2019, https://actiongraphicsnj.com/blog/4-principles-visual-storytelling/. (Module 2)

McIntyre, Karen E. & Gibson, Rhonda. “Positive News Makes Readers Feel Good: A “Silver-Lining” Approach to Negative News Can Attract Audiences.” Southern Communication Journal, vol. 81, no. 5, 7 June 2016, DOI: 10.1080/1041794X.2016.1171892.

Memou, Antigoni. Photography and Social Movements: From the Globalisation of the Movement (1968) to the Movement against Globalisation (2001). Manchester University Press, 2013. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21215w4. Accessed 28 Sept. 2020.

Midberry, Jennifer & Dahmen, Nicole Smith. “Visual Solutions Journalism: A Theoretical Framework.” Journalism Practice, vol. 13, 18 Nov. 2019, DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2019.1689371.

Mortensen, Tara M., and Peter J. Gade. “Does Photojournalism Matter? News Image Content and Presentation in the Middletown (NY) Times Herald-Record Before and After Layoffs of the Photojournalism Staff.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 95, no. 4, Dec. 2018, pp. 990–1010, doi:10.1177/1077699018760771.

Nachtwey, James. “My wish: Let my photographs bear witness.” TED, March 2007, https://www.ted.com/talks/james_nachtwey_my_wish_let_my_photographs_bear_witness. (Module 4)

The New York Times. “Staging Manipulation and Truth in Photography.” The New York Times, 16 Oct. 2015, https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/16/staging-manipulation-ethics-photos/. (Module 7)

Rankin, Tom. “Looking and telling, again and again: the documentary impulse.” Southern Cultures, vol. 22, no. 1, 2016, p. 3+. Gale Literature Resource Center.

Shurbaji, Eman. “Photo narratives: Defining picture stories, essays and packages.” Medium, 17 Dec. 2014, https://medium.com/learning-journalism-tech/photo-narratives-d77b812f99dd.

Thomson, T.J. & Greenwood, Keith. “Beyond Framing.” Journalism Practice, vol. 11 no. 5, p. 625-644, 8 March 2018, DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2016.1152908.

Thomson, TJ. “Mapping the Emotional Labor and Work of Visual Journalism.” Journalism, Sept. 2018, doi:10.1177/1464884918799227.